The Biodiversity Causes of the Ryukyu Islands

Twelve million years ago, the Ryukyu Islands were connected to the mainland. Geological processes between 12 million and 2 million years ago, such as the collapse of the Okinawa Trough, led to the separation of the Ryukyu Islands from the mainland. Fluctuations in sea levels connected and separated certain islands during this period.

The “Kerama Gap” between the Okinawa Islands and the Sakishima Islands and the “Tokara Gap” between Kodakara isaland and Akuseki Island were not connected to the mainland even when sea levels dropped due to their greater depths. As a result, the Ryukyu Archipelago were divided into three major regions: Northern Ryukyus, Central Ryukyus, and Southern Ryukyus.

Central Ryukyus, having been separated from the mainland the longest, preserved some species that had gone extinct on the mainland. Some of these species evolved into different species or subspecies on different islands.

For example, the venomous snake of the Protobothrops genus, which is distributed on the mainland, is also found in Central and Southern Ryukyus, known in Japanese as “Habu.” However, not all islands have Habu, and one hypothesis is that islands with lower elevations were submerged during the interglacial period, causing Habu to be absent. The northern limit of Habu’s distribution among closely related species in the Ryukyu Islands is represented by Tokara Habu (Protobothrops tokarensis), found on Takara isladn and Kodakara island, aligning with the predictions of biogeographical distribution boundaries.

In 2021, four islands, including Okinawa Island, Tokunoshima, Amami Oshima (all part of Central Ryukyus), and Iriomote Island (part of Southern Ryukyus), were designated as UNESCO World Natural Heritage Sites. The reason for this designation is the high biodiversity in these areas, reflecting the geological origins of the islands, making them crucial for protecting rare endemic species.

The Biota of Central Ryukyus

The three largest islands in Central Ryukyus, namely Okinawa Island, Tokunoshima, and Amami Oshima, are designated as UNESCO World Natural Heritage Sites. These islands were once connected as a single landmass, leading to similarities in their biota. For instance, the Ryukyu Tree Rat (Diplothrix legata) is currently the only surviving species in its genus and is found on Okinawa Island, Tokunoshima, and Amami Oshima.

Due to the prolonged separation of Central Ryukyus from the mainland, it boasts the highest proportion of endemic species. The percentage of endemic vascular plant species is approximately 8%, while for terrestrial mammals, it is around 60%, and for amphibians, it reaches about 90%.

These islands began to separate around 2 to 1 million years ago, resulting in some species undergoing further evolution into distinct species or subspecies due to geographical isolation. . For example, the genus Tokudaia evolved into Okinawa Tokudaia (T. muenninki), Tokunoshima Tokudaia (T. tokunoshimensis), and Amami Tokudaia (T. osimensis) on these three islands.

Tokunoshima and Amami Oshima, having separated more recently, exhibit a greater similarity in their biota. Both islands, for example, harbor the Amami Rabbit (Pentalagus furnessi). This species is extinct in its closely related species on the mainland and is another example of a genus with only one species.

Additionally, Okinawa Island is home to the Okinawa Rail (Gallirallus okinawae), the only flightless bird in Japan. Given that closely related species of the rail genus are distributed in Southeast Asia, this species may have originated from that region.

The Biota of Southern Ryukyus

Southern Ryukyus was connected to the mainland until it separated around 5 to 2.6 million years ago. Similar species that were once connected to the mainland evolved into distinct species or subspecies after the separation. Consequently, Southern Ryukyus hosts many species that are similar to those found in Taiwan or southern China. During the glacial period around 200,000 to 100,000 years ago, when sea levels dropped, it provided another opportunity for species to migrate to the Southern Ryukyu region. An example is the ancestor of the Iriomote Cat (Prionailurus iriomotensis).

The Yanbaru Region in Okinawa Island

Yanbaru (or Yambaru in the Okinawan dialect) is not a specific place name but a term that broadly refers to the forested environment in the northern part of Okinawa. In terms of well-preserved ecological areas, Yanbaru generally encompasses the northern three villages: Kunigami Village, Ogimi Village, and Higashi Village. It particularly refers to the area north of the “India Mongoose northward prevention fence” set up between Shioya Bay and Taira Bay. The core forested area in this region was designated as the “Yambaru National Park” on September 15, 2016.

The vegetation in the Yanbaru region is dominated by the Okinawa Castanopsis (Castanopsis sieboldii) of the Fagaceae family, constituting 70% of the biomass in Okinawa’s forests. It plays a crucial role in the Yanbaru ecosystem’s food chain, serving as a food source for species such as the Okinawa Rail, wild boars, and even freshwater crabs that feed on the acorns of the Okinawa Castanopsis. During the breeding season, the Okinawa Woodpecker creates nest cavities in these trees, and after the breeding season, owls and Ryukyu Tree Rats may use these empty tree holes.

The decaying wood chips produced from the center of the tree trunks serve as the growth substrate for the larvae of the Yanbaru Long-armed Scarab Beetle. Therefore, only forests with towering Okinawa Castanopsis trees can nurture the Yanbaru Long-armed Scarab Beetle. The intricate ecological interactions within the Yanbaru region highlight the importance of preserving this unique and biodiverse habitat.

Tokunoshima

Tokunoshima is located between Okinawa Island and Amami Oshima. The central and northern parts feature Okinawa Castanopsis forests similar to those in Yanbaru and Amami Oshima. However, the southern part is characterized by cave formations created from limestone, resulting in a distinctly unique geological landscape. The biodiversity on Tokunoshima is similar to that of Amami Oshima. Additionally, species such as the Tokunoshima Goniurosaurus (Goniurosaurus splendens) and the Tokunoshima Tokudaia (Tokudaia tokunoshimensis) can only be found on Tokunoshima.

Amami Oshima

Amami Oshima’s highest peak, Mt. Yuwan, stands at 694 meters, creating a cloud and mist zone with high humidity, fostering a diverse array of epiphytic plants. In the past, Amami Oshima and the northern part of Okinawa Island were connected landmasses, leading to similarities in the biota between the two. However, recent phylogenetic studies have gradually classified species on Amami Oshima as different subspecies or species from those on Okinawa Island.

For instance, a species that was once considered the Okinawa Ishikawa Frog (Odorrana ishikawae) along with Okinawa is now recognized as the independent Amami Ishikawa Frog (Odorrana splendida). The separation between Amami Oshima and Tokunoshima occurred more recently, resulting in similarities between the species on the two islands. However, certain species, such as the Lidth’s Jay (Garrulus lidthi) and the Amami Tokudaia (Tokudaia osimensis), are only found on Amami Oshima.

Iriomote Island

Iriomote Island is primarily composed of sandstone, and its coastline is predominantly covered by mangrove forests, making it the Japanese island with the highest diversity of mangrove species. The island boasts a high percentage of primary forest coverage, featuring numerous waterfall formations. Among the notable species on Iriomote Island, the Iriomote cat stands out as the most famous, with only around 150 individuals remaining, making it extremely rare. In addition to the Iriomote cat, the island is also home to species with similarities to those found in southern China and Taiwan, such as the Yellow-margined Box Turtle (Cuora flavomarginata evelynae) and the Sakishima Habu Snake (Protobothrops elegans).

Environmental Issues of World Natural Heritage

Small Indian Mongoose

In 1910, Okinawa Island introduced the non-native species Small Indian Mongoose (Urva auropunctata) to control the Habu population. However, the Small Indian Mongoose, which is diurnal, did not prey on the nocturnal Habu. Instead, it began preying on the chicks of the endemic Okinawa Rail, leading to a significant decline in the Okinawa Rail population. The distribution range also retreated northward. By the time the Okinawa government became aware of the issue, the Okinawa Rail population was reduced to around 500 individuals.

Since around 2000, the Okinawa government and the Environmental Agency have implemented a series of measures to eradicate the Small Indian Mongoose. These measures include anti-animal fences, various traps, search dogs, sensors, cameras, and more. Considerable financial resources and manpower have been invested. In recent years, the capture numbers in traps in the northern mountains of Yanbaru have also significantly decreased. However, due to budget constraints, the removal efforts are currently focused on the Yanbaru region. In other northern areas, even if there are other rare species, the presence of the Small Indian Mongoose is being overlooked.

Apart from Yanbaru, Amami Oshima also introduced the Small Indian Mongoose to control the Habu population. However, through years of removal efforts, the Small Indian Mongoose has not been detected for many years, leading to Amami Oshima declaring successful control measures.

Stray Cats and Dogs

Cats are natural hunters, and in Australia, feral and domestic cats without natural predators kill over a million reptiles each day. Research reports indicate that many species have become extinct or are endangered due to this phenomenon. The Australian government plans to cull two million feral cats by 2020. In Okinawa, in 2017, the fur of the endangered Okinawa Rail was found in the feces of stray cats. In 2018, cameras on Tokunoshima captured footage of a wild cat carrying a Ryukyu Tree Rat, highlighting the severity of the stray cat problem.

Organizations studying the Okinawa Rail have observed a decline in the bird’s presence in its usual habitats in recent years. Instead, it has been found in human settlements, suggesting that feral dogs, which have become wild in the mountains, may be hunting the Okinawa Rail. However, these dogs avoid entering residential areas, prompting the Okinawa Rail to seek refuge in human settlements. Unfortunately, this proximity to humans increases the risk of the Okinawa Rail being struck by vehicles. Feral dogs often operate in organized groups, making them challenging to capture, and conservation efforts face significant challenges.

In many tourist spots in Okinawa, stray cats and dogs are allowed to roam outdoors. While tourists often enjoy capturing the leisurely scenes of these animals against the backdrop of the sea, it is important to recognize that stray cats and dogs are not “wildlife” and should not coexist in natural environments.

Other Invasive Species

Apart from the Small Indian Mongoose, cats, and dogs, there are numerous other invasive species that have entered Okinawa through various pathways such as pets, goods transportation, and consumption. For instance, on Iriomote Island, feral goats, once domesticated, can now be observed climbing inaccessible cliffs in protected areas, potentially feeding on plants within the reserve.

Another example is the Taiwan Habu (Protobothrops mucrosquamatus) on the Motobu Peninsula. Originally introduced for the purpose of profit, including the production of beverages like Habu sake, the Taiwan Habu has escaped into the wild. Presently, most traps set in the Motobu Peninsula capture Taiwan Habu, surpassing the numbers of the native Habu snake.

Invasive species can lead to displacement effects on native species, such as more dominant competition for habitats or food resources, or predation on native species, resulting in a decrease in the population of native species. For example, the Yaeyama firefly (Pyrocoelia atripennis), native to the Yaeyama Islands, became an invasive species on Okinawa Island. The larvae of the Yaeyama firefly feed on a rare snail in the southern part of Okinawa Island, causing the near-extinction of this snail’s wild population.

Additionally, if hybrids are produced through mating between subspecies from different regions, it can lead to genetic contamination of local populations, disrupting the genetic differences established through long-term geographic isolation.

Invasive Species Control

Various local agencies are currently formulating measures to control invasive species. Here is a summary of recent initiatives:

| 2023/11/15 | A meeting was held to discuss the increasing population of feral goats on Iriomote Island and formulate measures to prevent their invasion into the roadless western part of the island. Currently, there are hundreds of goats on Iriomote Island. | Link1 |

| 2023/10/29 | Okinawa Prefecture Government and other organizations announced a feral cat management plan to protect the ecosystem. | Link1 |

| 2023/10/12 | Stakeholders in Amami Oshima met to confirm the current status of nature conservation issues, including invasive species and roadkill, and the implementation of relevant policies. | Link1 |

| 2023/9/9 | Okinawa AU, Biome, and other companies collaborated to use Starlink technology to improve communication in mountainous areas. An app is being utilized for the survey and monitoring of invasive species. | Link1 Link2 |

| 2023/6/29 | In the Yanbaru region, 1692 feral cats were captured over five years, with 1481 returned to their owners or successfully adopted. | Link1 |

| 2023/5/19 | The first discovery of the invasive species White-lipped Tree Frog was reported on Tokunoshima. | Link1 |

Controlling established populations of invasive species has already required significant financial resources and manpower. However, once introduced, completely removing invasive species is nearly impossible. The most crucial aspect of preventing invasive species is the conscientiousness of every individual—avoid taking local species, refraining from releasing invasive species or pets, and allowing native species to thrive in their natural habitats.

Roadkill

On many islands, public transportation is not very convenient. After being designated as a World Natural Heritage site, with the increase in tourists, traffic flow has also risen. The mountain roads, lacking traffic signals, are generally open, and some drivers unconsciously exceed the speed limit, especially after rainfall when amphibians like newts and frogs may appear on the roads. Predators such as snakes, birds, and even Iriomote Cats feed on these small animals. To prevent Iriomote Cats from scavenging roadkill, the authorities on Iriomote Island move the carcasses off the road. However, addressing the issue at its source by avoiding collisions with small animals is the fundamental solution.

Poaching

Rare species are often targeted by poachers. For example, Pieris koidzumiana has become extinct in the wild due to overharvesting, and it can now only be found in parks and gardening stores. The Red Crane Orchid (Phaius tankervilleae), Japan’s largest orchid, is another species in urgent need of conservation as its numbers have sharply declined due to poaching. Additionally, the Okinawa Dendrobium (Dendrobium okinawense), a unique species in the Yanbaru region of Okinawa, is also on the brink of extinction due to illegal harvesting. The Okinawa Crocodile Newt (Echinotriton andersoni) is a popular species in the illegal wildlife trade.

While there were regulations in the past, such as patrols on forest roads and a permit system for entering these roads, there was a lack of law enforcement personnel, and even if suspicious individuals or vehicles were present, there was no enforcement power to prosecute. Recognizing the severity of these incidents, the Ministry of the Environment took immediate action. In January 2019, the “Countermeasures against Poaching and Smuggling Liaison Conference” was established in Okinawa to address poaching. Actions include intensifying baggage scans by airlines and postal systems, and using apps to identify whether specimens are rare species, with a focus on turtles.

In Okinawa, the prefecture has implemented nighttime closures of forest roads during specific periods. During the summer, when beetle hunting is common, police patrol the mountains to prevent poaching. The prefecture is also working on formulating the “Okinawa Prefecture Rare Wildlife and Plant Protection Ordinance.”

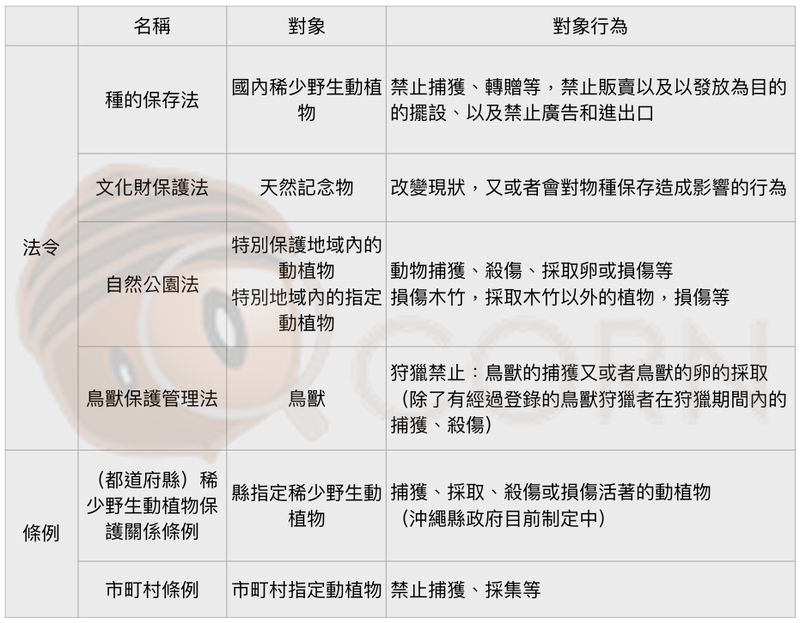

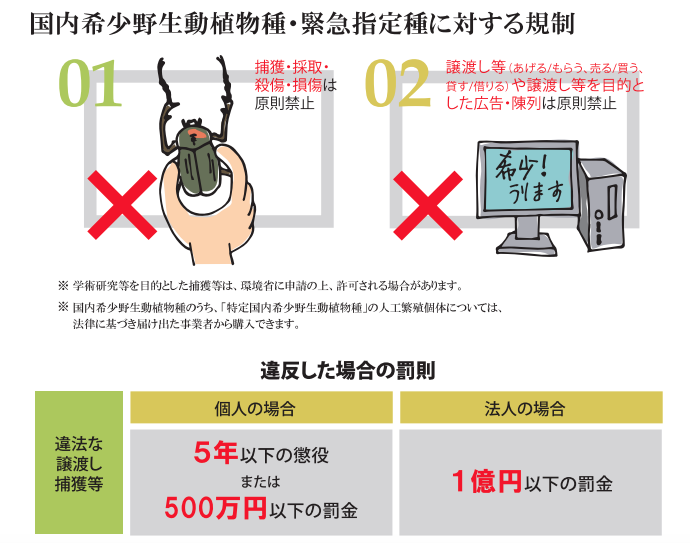

Poaching-related Regulations

Regulations related to the Ministry of the Environment can be referred to in the diagram. If individuals are found illegally capturing wildlife, they may face penalties of up to five years in prison or fines of up to 5 million Japanese yen. When engaging in observations on islands designated as World Natural Heritage sites, such as Yanbaru and others, only take photographs and refrain from removing plants and animals! If you observe any suspicious individuals or vehicles, please immediately contact the Ministry of the Environment or the nearest police station. Let’s work together to safeguard the various plants and animals residing on these islands!

Poaching-related Reports

| 2023/11/3 | To prevent poaching of rare species, an agreement was made by the Japan Ministry of the Environment, Okinawa Prefecture Government, and police to conduct nighttime patrols on forest roads. | Link1 |

| 2023/8/19 | To deter poaching, certain forest roads in Yanbaru will be restricted from August 25 to October 27. | Link1 |

| 2023/6/16 | Two Chinese tourists were found with 682 Purple Land Hermit Crab, a natural monument. | Link1 |

| 2022/12/21 | Two Korean tourists were caught smuggling six Okinawa Crocodile Newt at the airport. | Link1 Link2 |

| 2022/6/13 | Japanese was arrested for selling Okinawa Crocodile Newt online. | Link1 |

| 2019/4/8 | The manager of a Tokyo pet store was arrested for smuggling rare species from Amami Oshima. | Link1 |

| 2018/10月 | A Japanese illegally transported 60 Ryukyu Black-breasted Leaf Turtles to Hong Kong. | Link1 |

The Environmental Impact of Tourist Crowds

With the registration of these four islands as World Natural Heritage sites, there has been a significant increase in visitors to the area. Without proper control over entry into the forested environment, there is a risk of environmental degradation, which could be detrimental to ecological conservation. Therefore, eco-tourism should be subject to reasonable restrictions, and visitors should explore these areas with certified local ecological guides who are familiar with the environment. Currently, various regions have licensed guides, with some locations allowing entry only with certified guides, while others require advance permission.

Increase or decrease in specific species leads to ecological imbalance

The following is my personal opinion. Despite the existence of serums, Okinawans still harbor a strong aversion to Habu snakes. Locals tend to kill Habu snakes upon sight to ensure they “do not pose a threat to others,” overlooking the crucial role Habu snakes play in the ecological food chain. For example, on Amami Oshima, the Amami Rabbit population has significantly increased due to successful efforts in controlling introduced species like cats and dogs. However, the natural predator, the Habu snake, is targeted, leading to a drastic reduction in the Habu snake population. This reduction hampers their effectiveness in controlling the Amami Rabbit population. Currently, the Amami Rabbit population has exploded, causing an alternative ecological disaster as they consume rare plants in the forests. It’s akin to a replay of the incident where the Hokkaido wolf went extinct. I believe Japan should abolish the bounty system for Habu snakes, educate the general public about the importance of Habu snakes in the ecosystem.

Explore Yanbaru and World Natural Heritage Islands